How to build an effective 100-day new CMO plan

Framework for CMO 100-day plans: assessment approach, quick wins, strategic planning, and stakeholder alignment.

By Maria PergolinoThe thing about your first 100 days as CMO is there is no step-by-step playbook. No two companies are alike enough for the same plan to apply—and that includes your competitors. Your plan must be custom. That’s why instead, I’ll prepare you the next best way, with the specific tools for drafting your own 100-day plan using external research (including a spreadsheet template) and strategies for conducting internal interviews.This is a great exercise for those considering joining or who have just joined a new company. It is also a wonderful yearly refresher for seasoned CMOs. If this process leaves you convinced of a few things, I hope it’s this: That marketing’s job is to bring the “market” lens. That you can’t delegate this type of understanding. And that all you need to arrive at the right answers is to interview and research with purpose. Let’s dive in.

Conduct your internal interviews with purpose

The reason it isn’t possible to produce a canonical “100-day CMO playbook” is you can't talk about plans without knowing what you hope to achieve. What you hope to achieve should derive directly from the company’s top goals. That’s step one. Know those goals. You probably already have a good grasp on these from the interview process, but it’s imperative that you understand the company:

- Vision

- Mission

- Top objectives

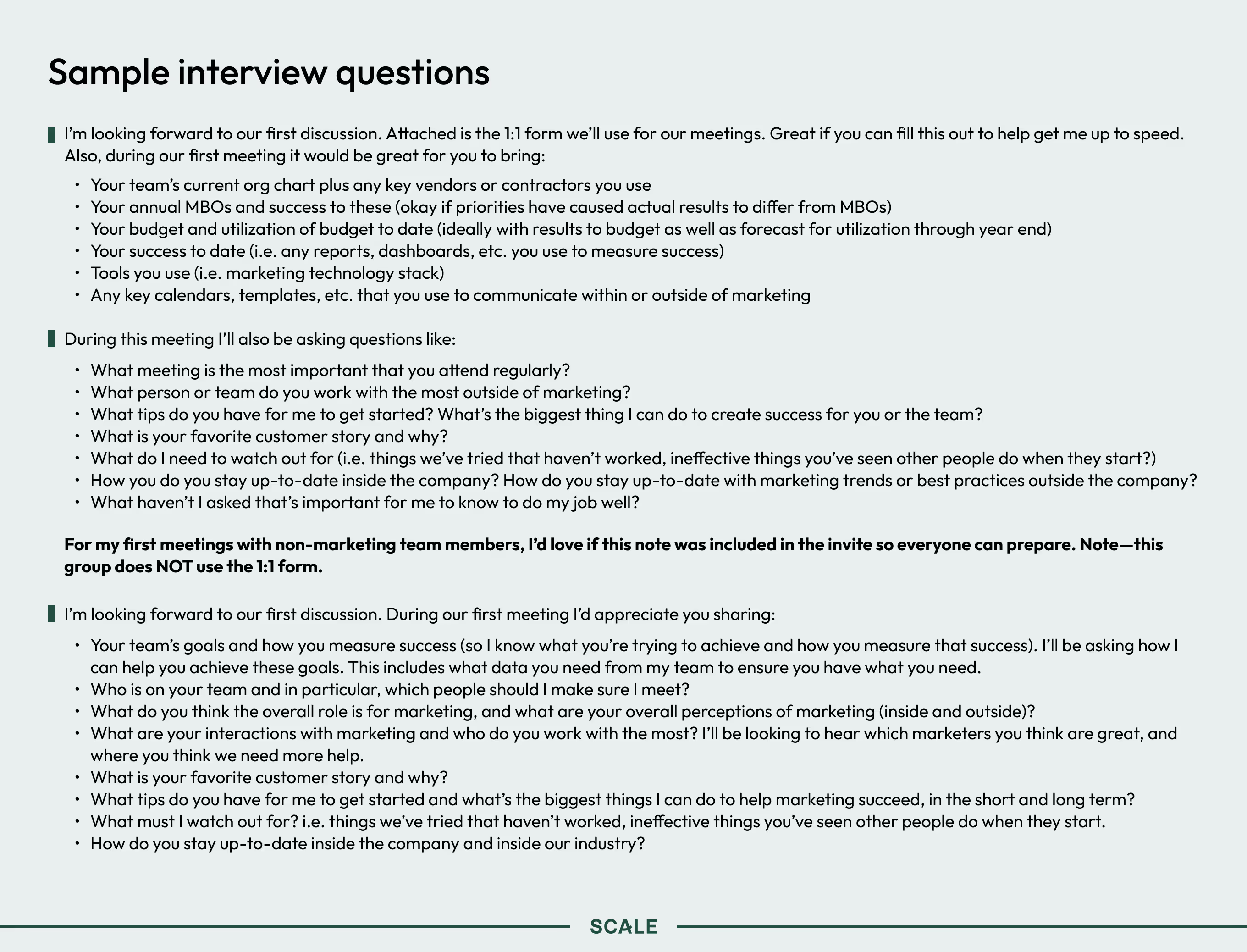

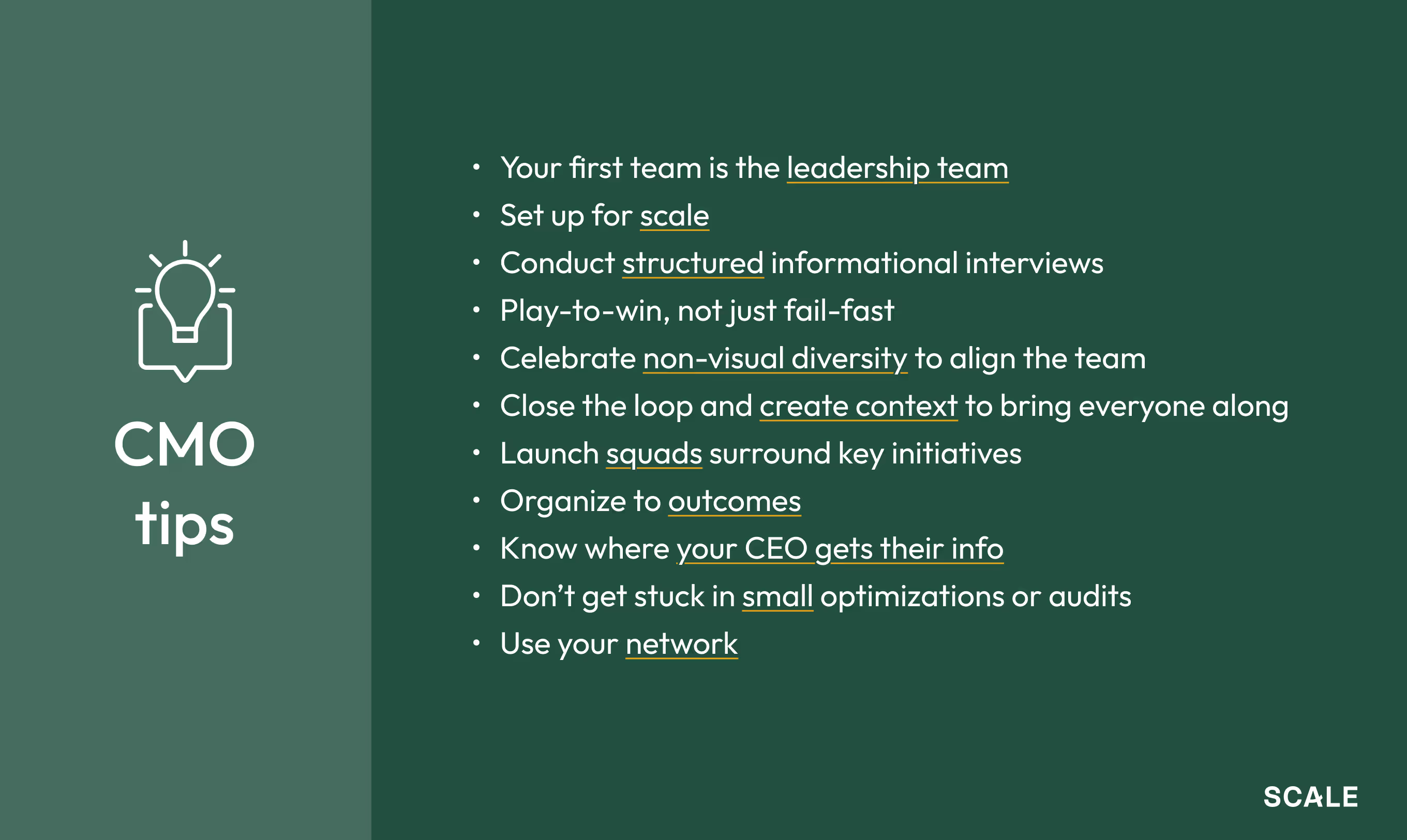

Get them from top leadership and compare people’s answers. Hopefully, those answers overlap enough to form a clear direction, otherwise you have some digging to do.Next you’ll need to know how the company is built—how teams are organized, how they make decisions, and where people draw insight from. Interview all the people on your team and your partners on related revenue teams to understand what you do and do not yet know. I know I can’t talk to everyone, so I like to send a wide survey, as well as conduct specific interviews where I ask people to come prepared.I say “interview with purpose” because you really do need to use this time wisely. You should be entering with hypotheses to prove or disprove, and digging to figure out what more there is to explore along with what you don’t know. “With purpose” means asking your interviewees to prepare things they won’t know offhand (see below) and leaving with clear answers to most of your questions.

Of course, you will only ever find about half of what you need talking to people who work there. The other half of the story is outside the company’s four walls. Because while product, sales, and customer success probably spend almost all their time looking within, events are happening outside. Markets are contorting and reforming. Your job is to look without and know that. If you remove the “-ing” from your title, that’s one of your most important jobs—to understand the market. You champion that outside perspective.

Begin your corporate planning process

When I understand the company and the market and have developed some hypotheses, I build a marketing plan, starting with … nothing. Just a blank slate. I don’t presume any team members or tools or workflows will remain constant, because the question is, how are we going to help the company achieve its objectives?From this perspective, I believe in zero-based budgeting. For those not familiar, this is the process of rebuilding your budget after each period (year) and not assuming any expenses are coming forward. It helps ensure every marketing dollar is put to work, and forces difficult decisions around what belongs and what doesn’t.I also know I’m in good company with other effective CMOs when I say that finance does not decide your corporate plan. You do. Finance should help you figure out how to achieve it. No business wants to spend several million on marketing for marketing’s sake—they should want to drive $50 million in revenue, and finance should then allocate the money as part of a conversation with marketing about how everyone’s going to achieve that together.

Alas, this isn’t how it works at every company. Finance often leads. But I truly don’t understand how companies can set budgets without the market voice in there.

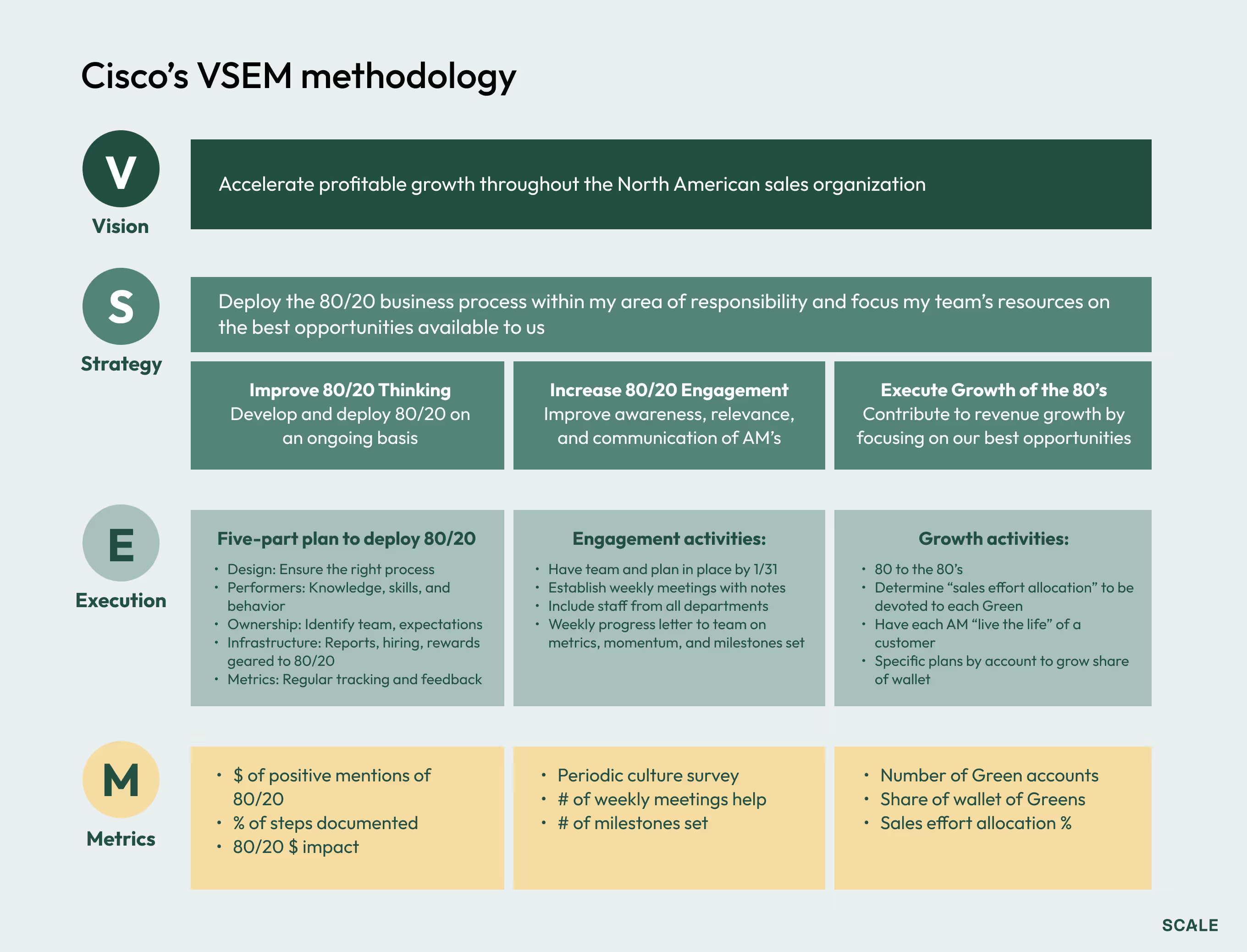

Vision planning with VSEM

I really like Cisco’s framework Vision, Strategy, Execution, Metrics (VSEM) for its simplicity, and use objectives and key results (OKRs) in tandem. There are many good alternatives to these frameworks, but in VSEM, you start with the vision and mission of the company, then bring it down to a strategy that is a two-to-three-year plan. Then you break that three-year plan into one year and the big, cross-functional things to accomplish. That’s where OKRs can take over and you can document what everyone’s key results are over the next year, which tie your metrics.

This should happen with all the C-level functions present. And as the only one with a verb for a title (“market-ing”), you bring that active outside awareness of what’s happening in the market. Together you decide what you’ll do internally and externally to execute.

The best 100-day plans do not state the obvious. They don’t have time for that. I reviewed my own past 100-day plans to write this, along with those of Carilu Dietrich, Mini Peiris, and Sydney Sloan, and they all skip directly to making a bold, counterintuitive assertion about the future.For example, “If the company does not do X, the entire enterprise is at risk.” Then, the whole plan focuses on getting that done.That’s a rallying cry. That’s clarity. I call them “external assertions” because they’re rooted in what’s happening without—and how your organization must adapt to meet that moment. It also doesn’t hurt that an assertion framed in that way makes for a highly memorable hook.Example external assertions:

- We must differentiate from these two competitors or else.

- We must be seen as “human plus AI,” not just AI, or we lose.

- If we cannot overcome our legacy perception in 18 months, it’s over.

It may go without saying but it’s easier to get budget when you’ve brought your other C-level partners along in developing your plan. When you present this assertion, it’s always clarifying. Maybe your CEO says, “Yes, that’s it.” But also, maybe they say, “No, I think you’re seeing the category issue wrong,” in which case, perhaps you are not the right person for them—and you do want to know that now.

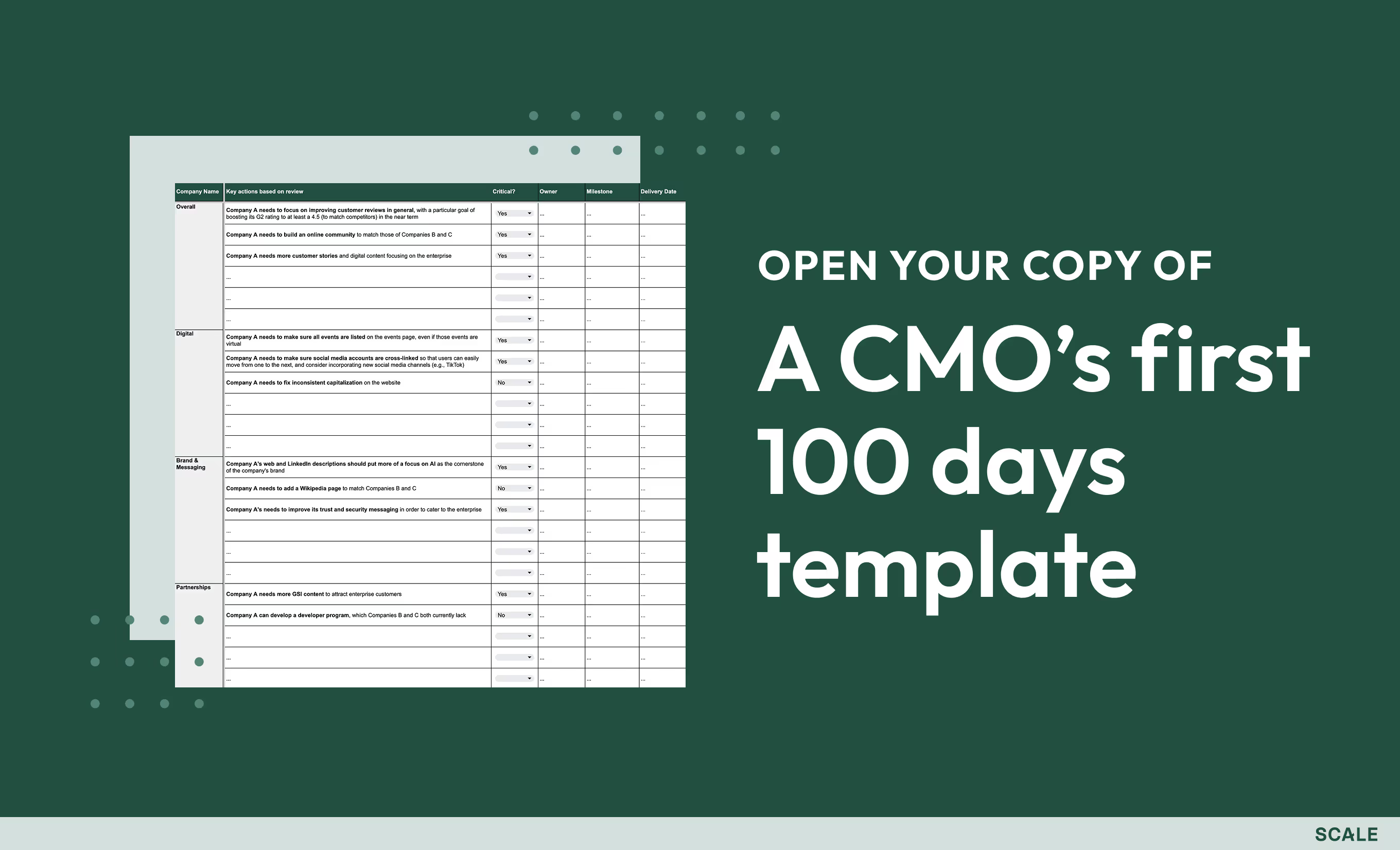

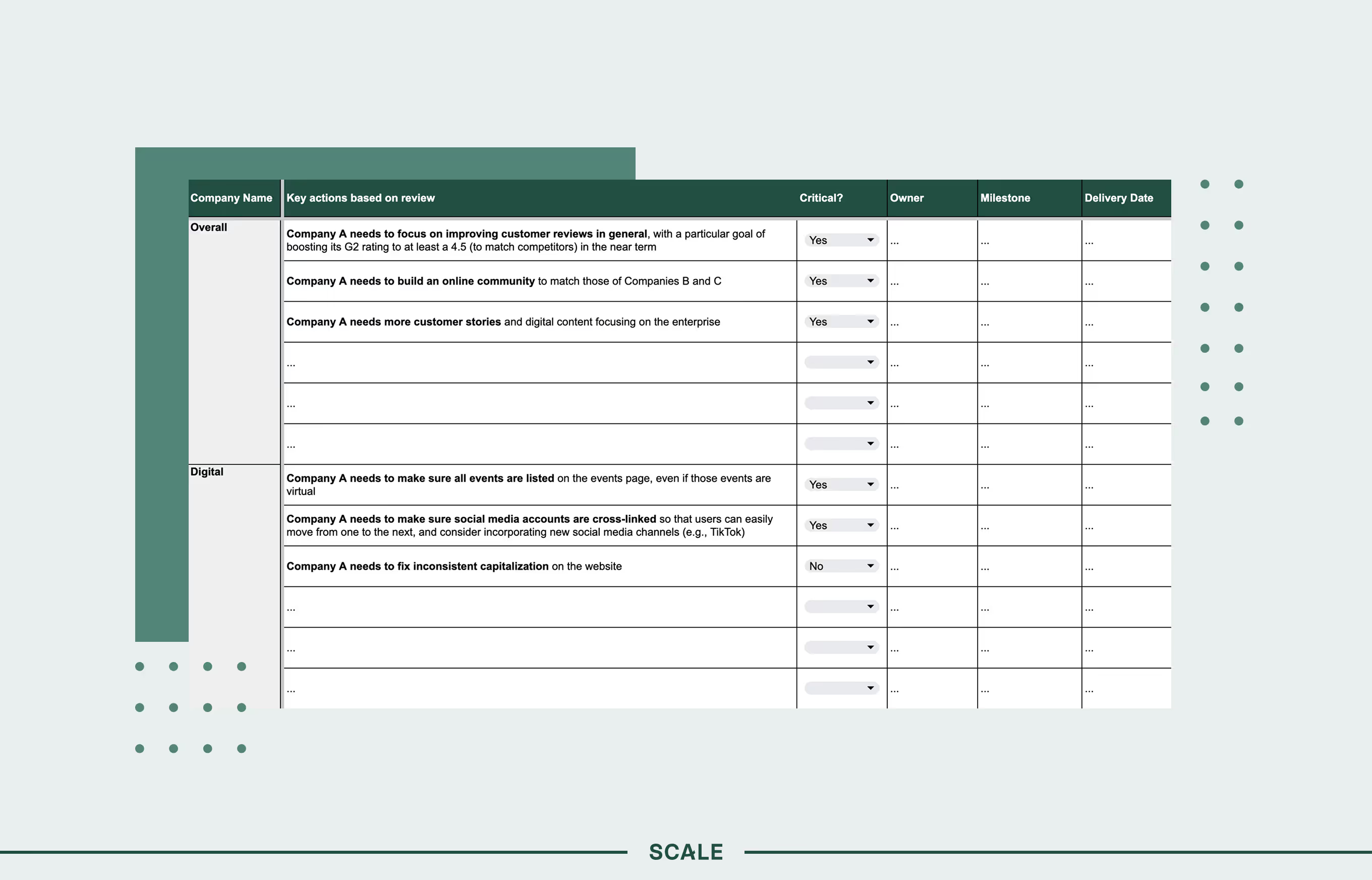

Conduct your market analysis

Once my assertion is drafted, I then spend a few days examining our competitors to complete the market spreadsheet (template below). For this, I’m looking at their website, how they present themselves on LinkedIn, what ads they’re running (search Meta’s ad library, LinkedIn’s ad library), what customers they list—everything public. Maybe all your competitors don’t state how many customers they have. What does that say? I note all the marketing tactics they’re using. Who are they partnering with? What are they doing with affiliates? Can I find any agencies they’re using? I look at review sites, especially Glassdoor. Nobody will tell you more about what’s wrong with the product or how they’re misserving customers than disaffected employees.

With product review sites, look at where you rank the highest. If you are top-ranked across all, that’s a great message to go to market with: “You cannot find a place where competitors rank higher than us.”This whole market exercise will tell me, to some degree, how threatened competitors are by us, and how important we are to them—by virtue of the branded keywords they’re running ads against us and whether they’ve created competitive pages.As I go through, I’m noting my recommendations as they arise. I gather them all at once, then return later to sort, rank, and delete the less important ones.

This information grows especially powerful when you repeat this exercise multiple years in a row. Sure, follower count is a vanity metric but if a competitor is growing that rapidly on all fronts, it’s a sign of momentum. I’ll also find issues with our own marketing like dead pages and messaging that’s soured. It’s a great way to emerge with a list of 10 quick wins.That’s really what you want in your 100-day plan: 10 low-effort things they could change to suddenly alter the direction of their market presence. Followed of course by longer-term goals that will really address your external assertion, like that you want to pursue a category. But your quick wins build up social capital to spend on the things you know matter.

Staff your team

As with all planning, I begin my staffing assessment with no assumptions. Instead, I build the org chart I think we’ll need to achieve our objectives. I look at roles, budget, and jobs to be done and then I sort the people we have—“Oh, we actually need a director over here and dollars over there.” It’s of course messy, as you aren’t going to let a coordinator go because you suddenly need a director. But you’re making plans to move the right people into the right seats.Set the expectations upwards, too—let your CFO know that you don’t yet have the director you need but will be back asking for more budget when you’re ready, so it doesn’t look like you’re changing your mind. Nothing builds credibility like things going exactly as you foretold.

Build a team that doesn't need you

Ideally, you want to create a plan where you do not own any individual tasks; you will not have time and you cannot fill in for missing people. That’s the kind of plan that will actually carry through. At the same time, expect that any unassigned tasks that arise will ultimately fall to you. I was working with founders the other day who said, “Those roles aren’t assigned,” and my response was, “If it’s not assigned, it’s yours.” If it’s needed to hit the objective, those jobs need to be done. If you find you must inherit jobs, know that area is a big risk until you find someone to own it.

Start your weekly team meeting now

Kick it off before you need it so it becomes habit. At Apttus, I started the weekly meeting when it was two of us, and when the growth really kicked in, we didn’t have to redo anything. The meeting already existed and as we added people, it was habit.As with the other parts of this process, I like to review my meetings annually. I ask people what meetings they feel are important and, like with zero-budgeting, to assume none will continue unless they continue to be valuable.

Play to win rather than fail fast

I come into a lot of organizations to find they have set assumptions holding them back. They say, “Webinars don’t work for us.” But suppose that my market review shows webinars are working for all our competitors. So maybe it’s not that they don’t work. Maybe it’s that the team failed too fast. We didn’t execute well. I’m not saying everyone has to run every type of program. But part of your job as chief outsider is to help everyone reset untested assumptions and pick from that full strategy checklist. Pick the few places you know you can play and win.

Don't get mired in small optimizations

You made a big bold external assertion, which your “10 low-effort” tasks level up to. Now it’s your job to stay at that level. Don’t get stuck in small optimizations. One marketing leader I spoke with recently was spending a lot of effort trying to optimize their funnel. But their numbers were so small, their results didn’t really mean anything. They should have simply focused on getting enough people into the funnel to begin with.One way to avoid getting buried in minutiae is to start every meeting with the hardest thing on the agenda. Everyone likes to save that for last. Tackle it first. Sometimes when you solve that, the other things don’t matter or they fall into place.

Write your 100-day plan

With all the above research and preparation, record your plan on paper, ideally on one page. If you can’t make the plan make sense on paper, it certainly won’t make sense in reality, when other people who are not you have to apply it.

Conduct a preemptive retrospective

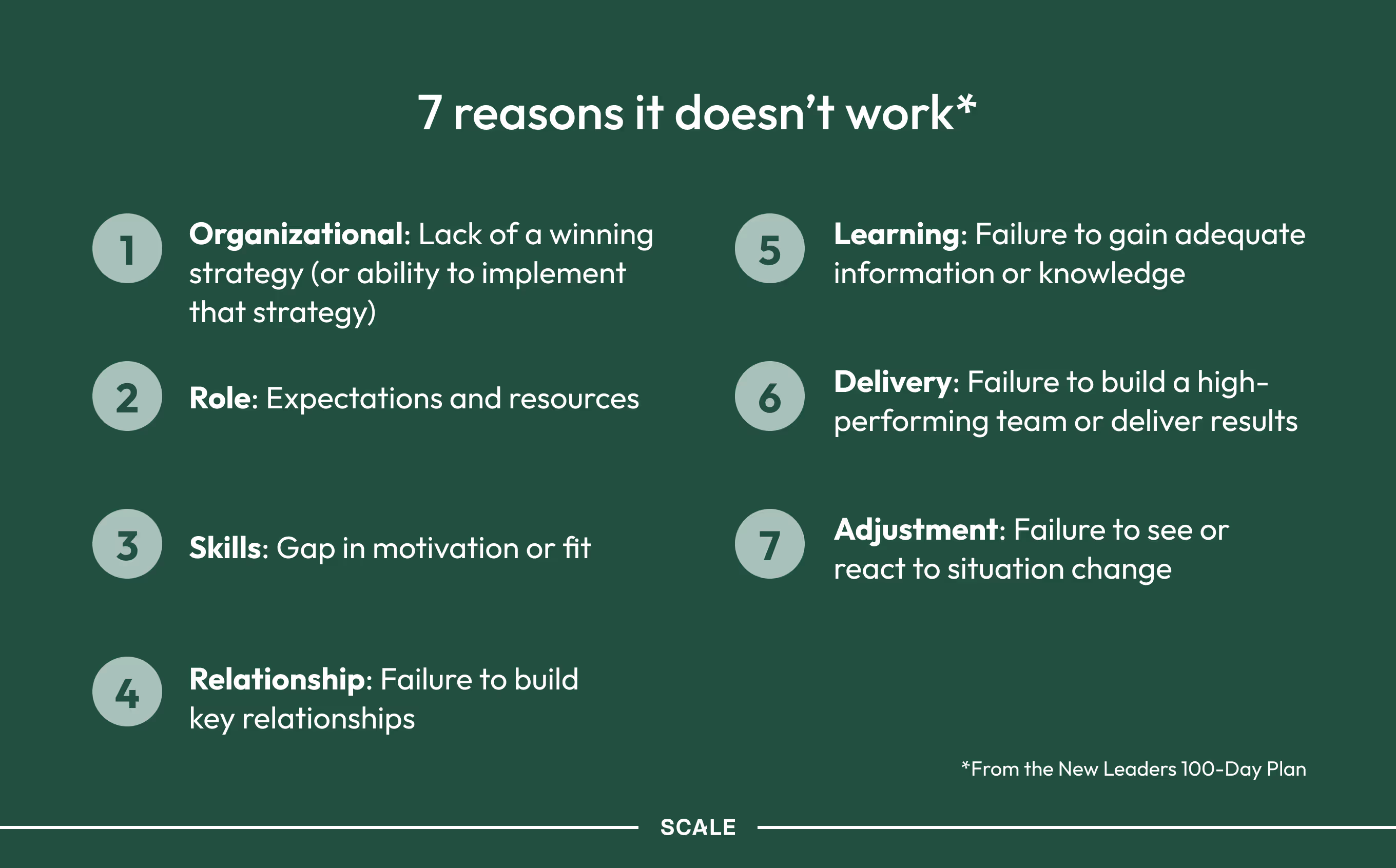

Here’s a final exercise: Pretend your 100-day plan didn’t work. Write its eulogy. In other words, what are your greatest “fears” with what could go wrong? I find that’s a valuable exercise because it can lead you to seek help in areas you or your team are weak, and to not let those issues fester. Sometimes you don't have the right skills, but you can hire. Sometimes you didn’t build the right team, but you can ask advisors. Don’t let those fears go unaddressed.

Finally, after it all, check in with yourself. Sure, the company is in the right place. But are you? That personal aspect and your ability to execute are as important as anything happening within the company as without. It’s internal, it’s external, and it’s personal. Assess all that and you’re ready for your first 100 days. Feeling unsure about your plan or have questions? Reach out to me, I always love chatting with new CMOs.

News from the Scale portfolio and firm