How reinforcement learning is upending the AI infra stack

AI breakthroughs are always coupled with a data source. Imagenet was a precursor to Google photos and self-driving cars. ChatGPT came about because humanity took to the internet and accumulated 175 zettabytes of information. So if you’re building the next AI breakthrough you have to ask, what’s my data source? And unfortunately, that’s proving scarce.

In this talk from TechCrunch disrupt 2025, Eric Anderson, Partner at Scale Venture Partners, and Kyle Corbit, CEO of OpenPipe, share why they believe reinforcement learning is the answer. It can generate a stream of unique and ownable data that makes lower cost, typically less accurate models outperform better ones. In their view, reinforcement learning will eat the whole training market.

We have but one internet

Compute is growing, but that’s of no value to AI startups unless they have more data to work with. And unfortunately, data is a fossil fuel—we accumulated that entire internet worth of material over 40 years and have essentially blown through it in four. We have but one internet, as Ilya Sutskever, co-founder of OpenAI, has noted.

This means we’re going to need a new and more renewable data resource.

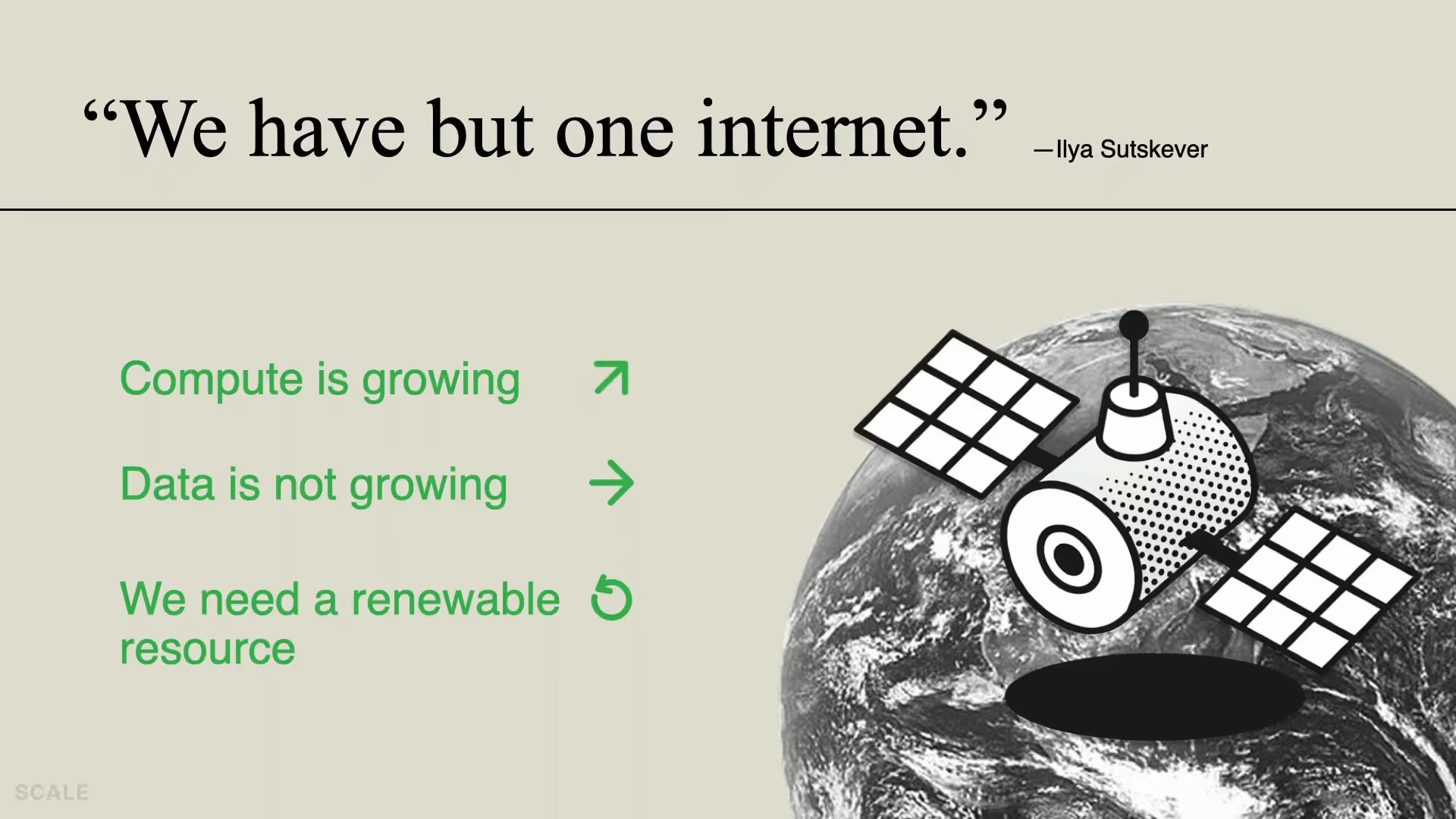

We can look to Google’s algorithm for inspiration, because it’s the second, hidden algorithm that helped make Google the dominant search engine provider. (Google still has 90% of search market share at the time of writing, for those keeping score.)

There is of course Google’s Pagerank, which we all know: It scrapes the open web and analyzes page content and backlinks. This is fossil fuel—every search company has access to essentially the same dataset. But there is what we’ll call Google’s “algorithm two” which farms data from user interactions. Every click, back button tap, and page scroll gets captured and adds to a second, owned repository that only Google has access to. Pagerank’s data is a commodity. But algorithm two’s data is infinitely renewable and becomes a monopoly subject to network effects. It eventually locked out competitors.

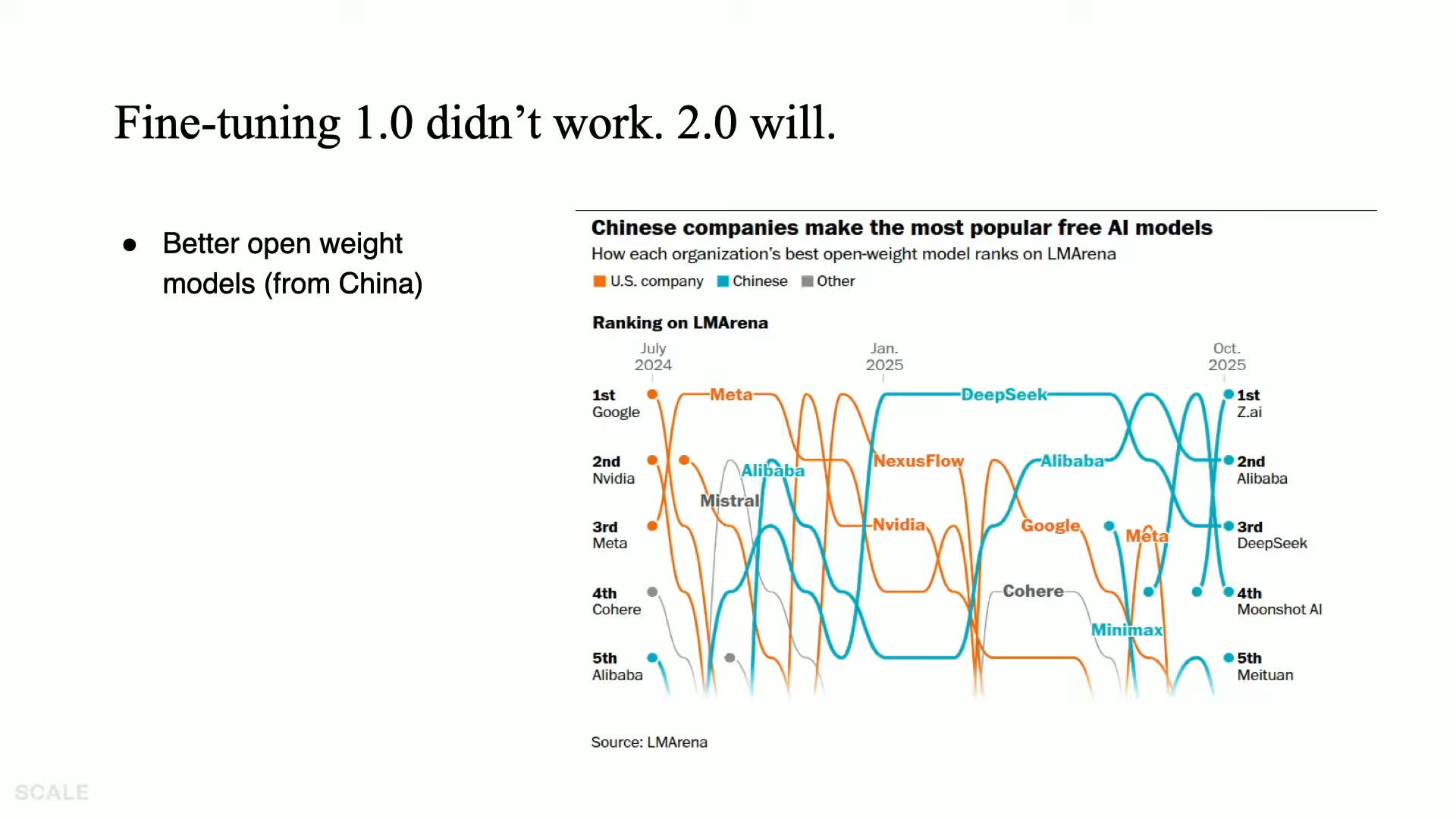

LLMs are in a race to develop their own algorithm two. Today most are still relying on Pagerank-type latent data on the internet but as we have seen, anybody, including teams in China like DeepSeek and Alibaba, are producing equally good models. Any provider that developed an algorithm two could, theoretically, lock out the competition, which is why reinforcement learning is pushing the frontier.

How have models done it thus far? OpenAI used reinforcement as far back as 2022 with ChatGPT 3.5, to inject human feedback into the models and help them communicate. Two years later, we saw 24 reasoning models come out.

These were reinforcement models tuned for additional reasoning. In a sense, doing their own context engineering. They think, request additional information, think more, then request additional context. The next step of this is agents that learn from interacting with their environment.

Consider a container like Excel, Salesforce, or a travel website. Within that environment, there are controls and there are user goals and a reinforcement algorithm with a reward model can optimize itself for positive outcomes. With these models, purpose-built agents perform much better—with a catch. The results aren’t generalizable outside that container. Meaning, unlike a human, no matter how completely the model masters a maze, it can’t then apply that learning to the next maze. What it learns from Excel, it cannot apply to a Salesforce report.

So, environment interaction works, but not for the foundation models. Which actually might be okay, because they do work for purpose-built agents—which may be enough to achieve a lot.

Fine-tuning 1.0 didn’t work, but we believe 2.0 will

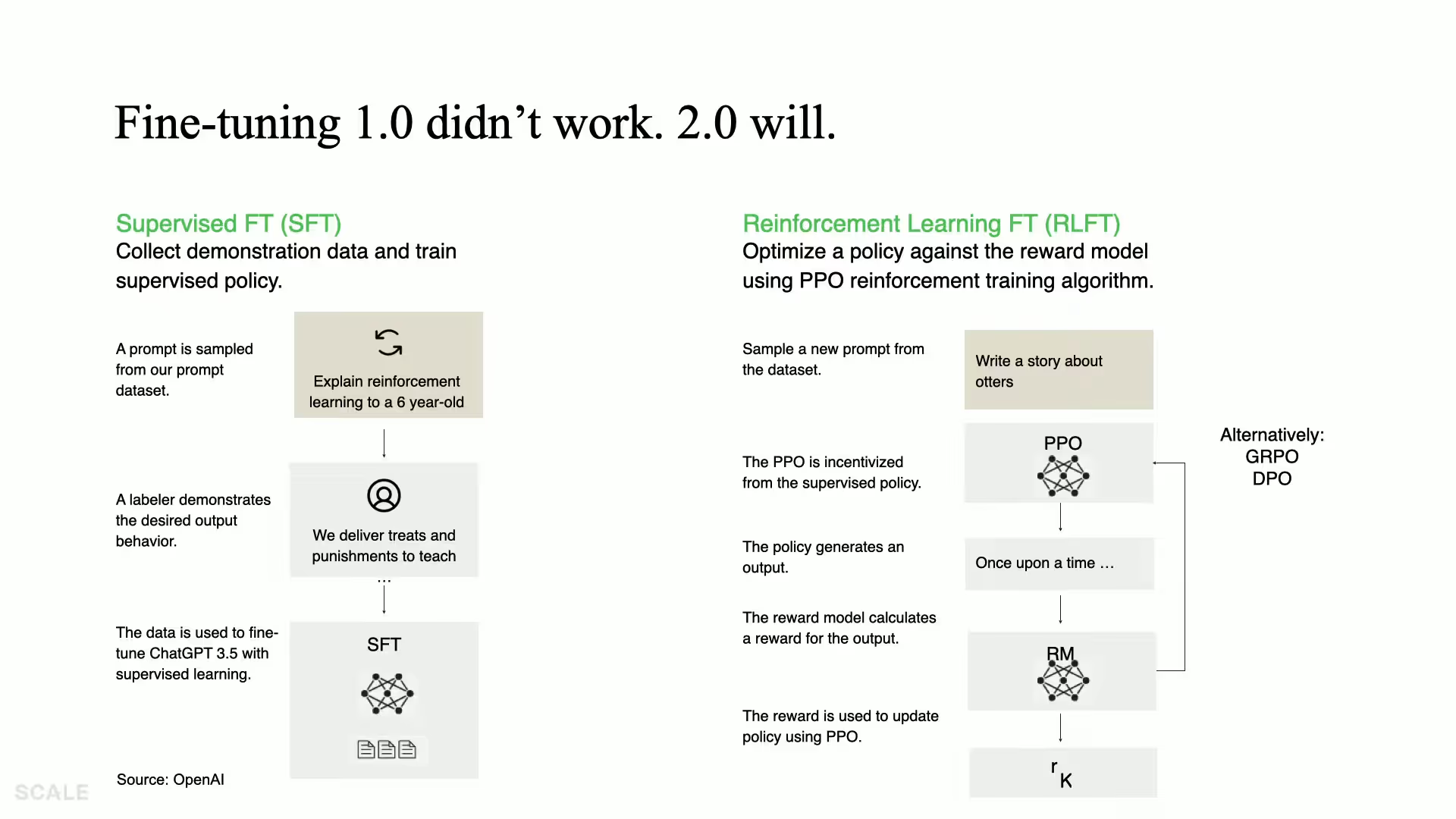

If all this sounds suspiciously like fine tuning, you are right. It has similar ergonomics. Fine tuning has been around for five years and traditionally has meant supervised learning—you give the model a labeled set of prompts and response pairs. Pictured is a graphic from ChatGPT explaining how their model works.

It certainly makes the model faster, and possibly cheaper, but what people really wanted from these early models was better responses. It’s unclear if fine tuning achieved that. What is working now is the new reinforcement learning algorithms, pictured. We also have better open weight models. China’s models have surpassed Llama, the standard for a while, and all of this sets the stage for how we can fine tune agents to perform better.

Case study: Using reinforcement to help you search your inbox with natural language

In this series of tests, the OpenPipe team presented an example of specialized, fine tuned agent trying to search an inbox. Let’s assume you give it access to your Gmail and tell it to look up what time the baseball game is on Friday.

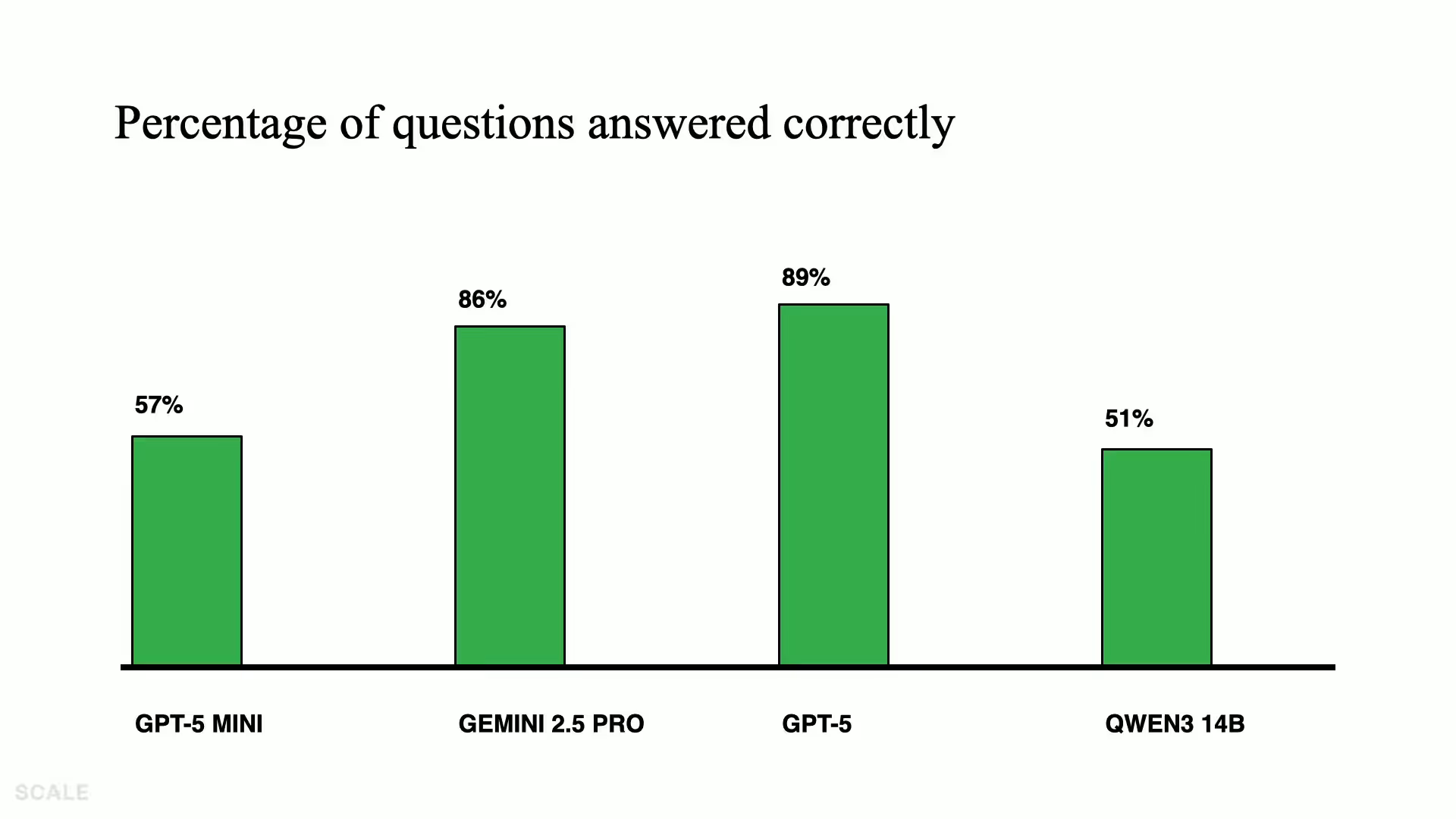

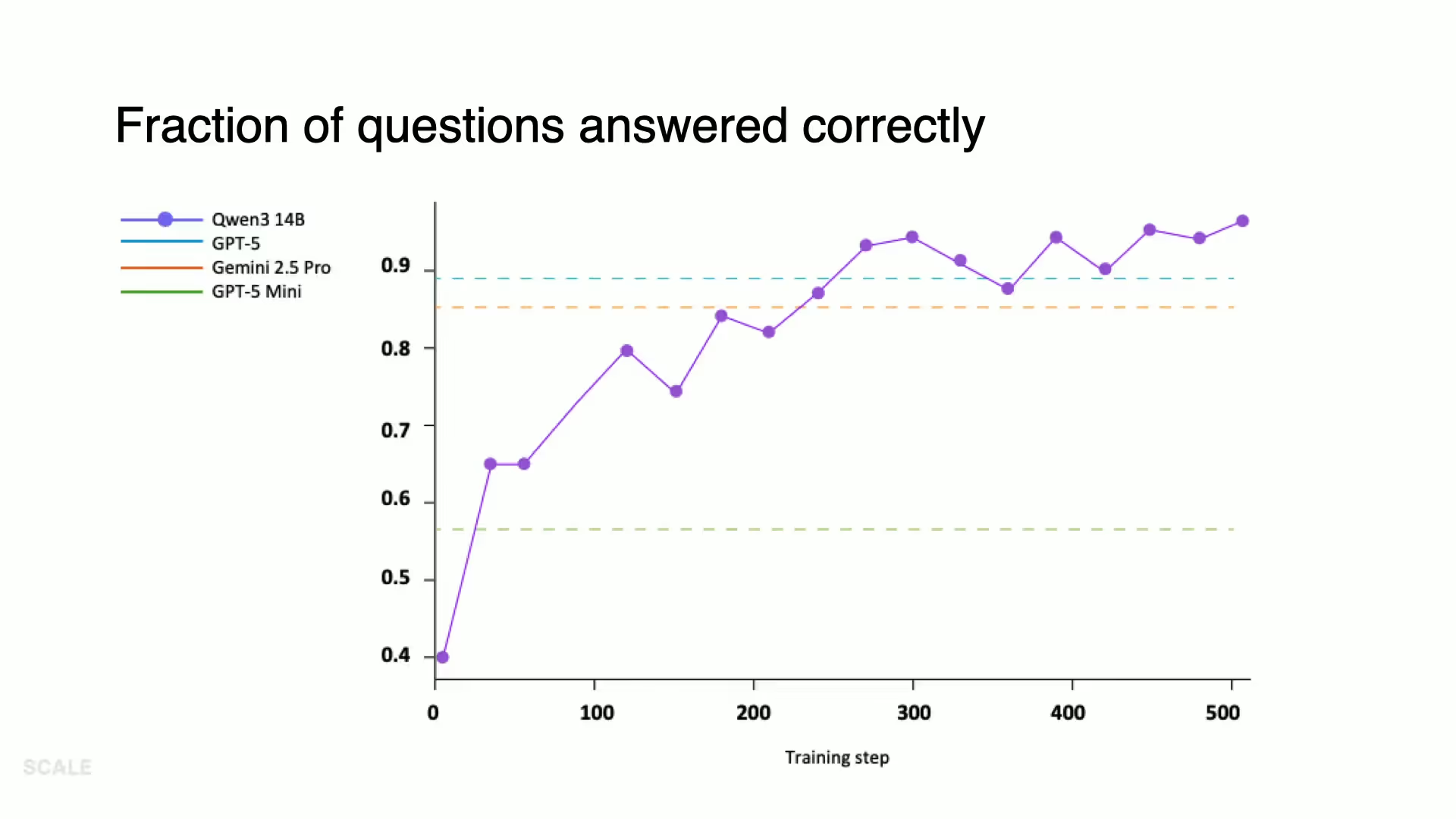

Pictured are each model’s odds of success. Note how QWEN 14B underperforms. Relatively speaking, it’s lightweight and cheap and this is what you might expect.

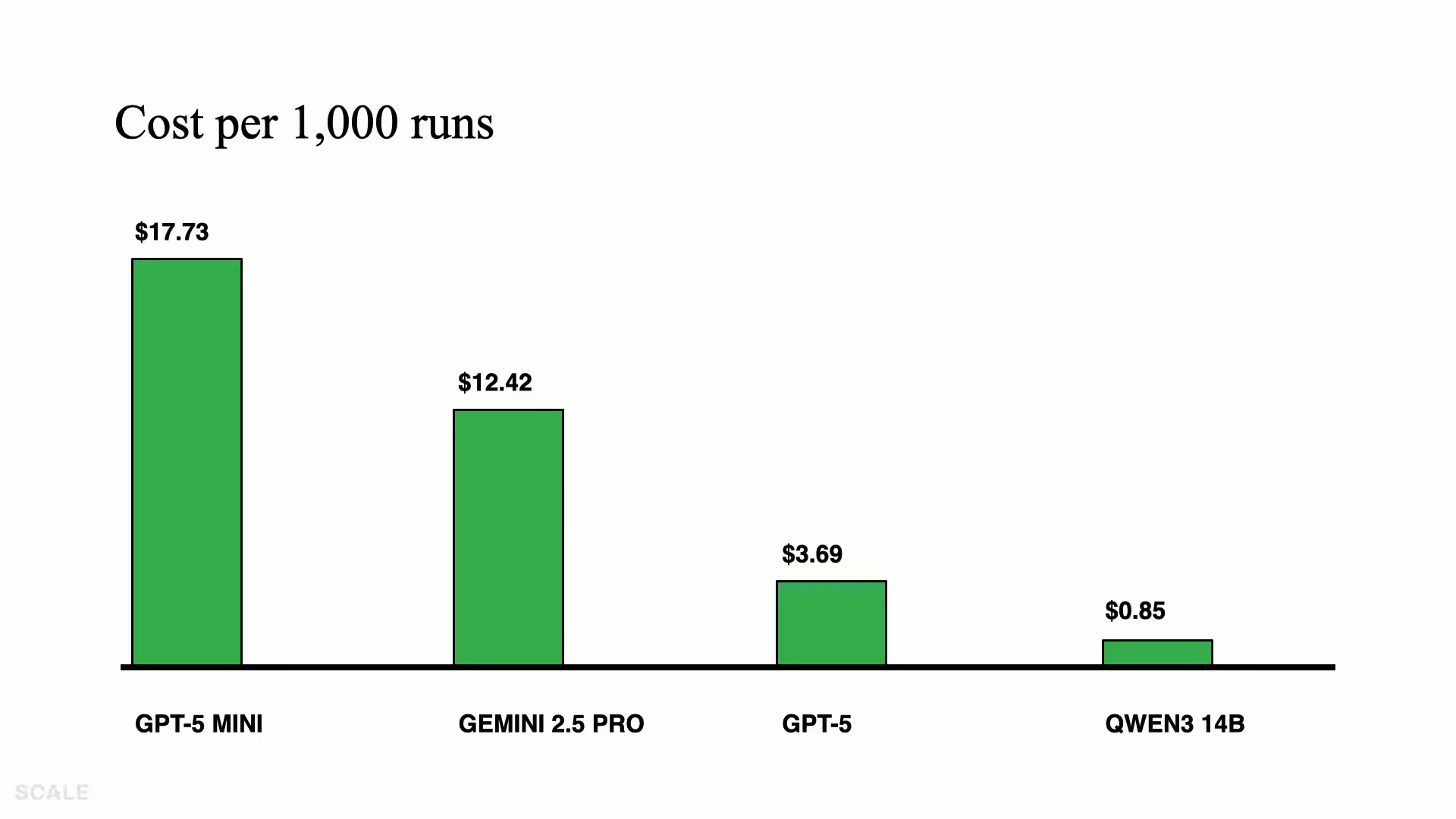

Though actually, upon reflection, cost is a relevant factor in this search because as product people, we care about more than just accuracy or reliability. Cost and latency are important levers in creating a satisfying user experience. And here we see, QWEN 14B’s costs two orders of magnitude less than GPT-5 Mini.

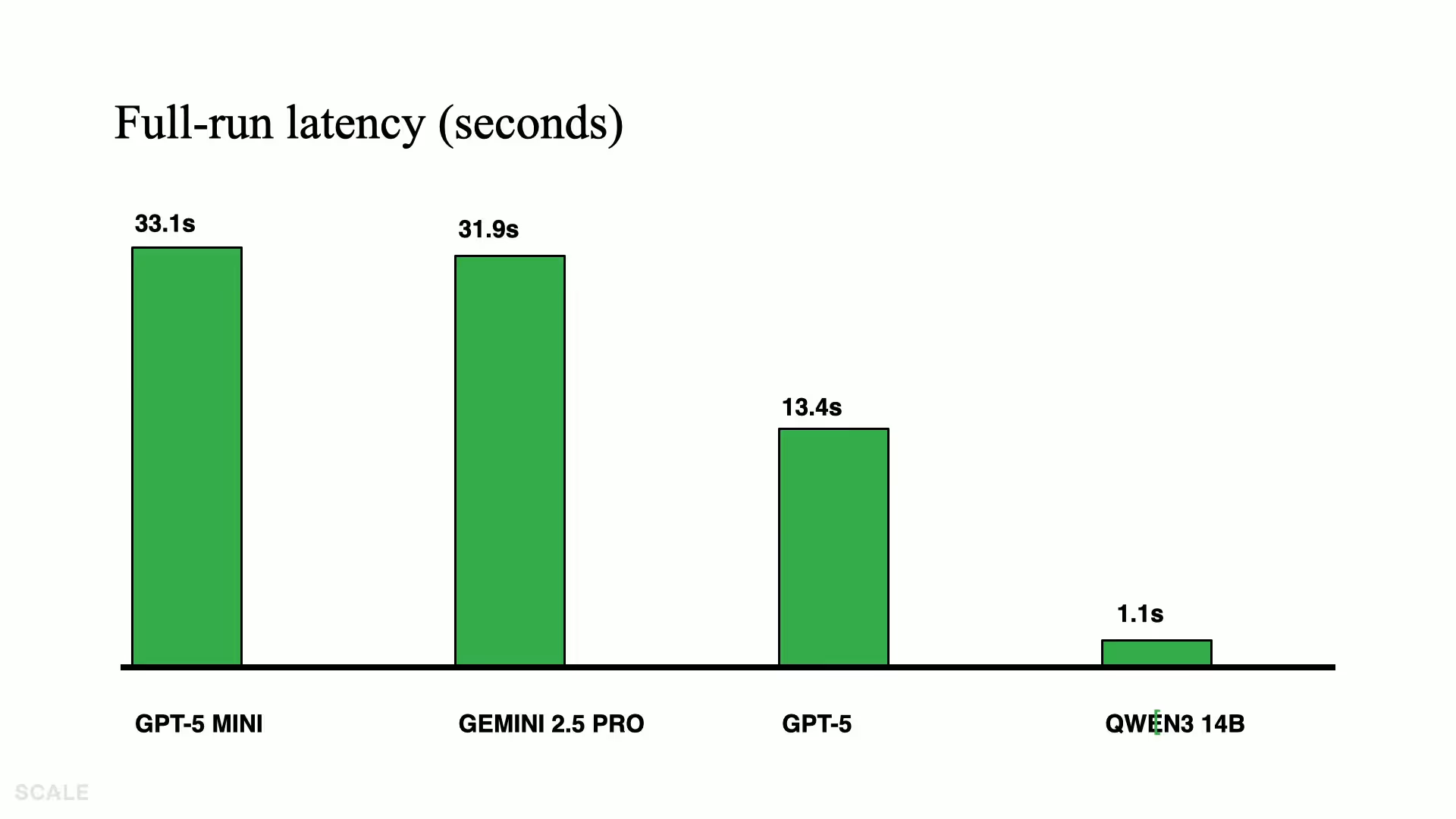

QWEN 14B is also far more efficient on latency. It returns a response 30x faster than some of the other models.

What good is better speed and cost if it gets the answer wrong half the time? Well, if we let QWEN 14B explore and try the task a bunch of times and reinforce its own learning, it quickly surpasses all other models. It’s as if it’s living at hyperspeed, and though it does not initially know the task, it can run a dozen simulations before other models have finished thinking, and become an instant expert.

Implications for the market: Post-training will eat inference and evals

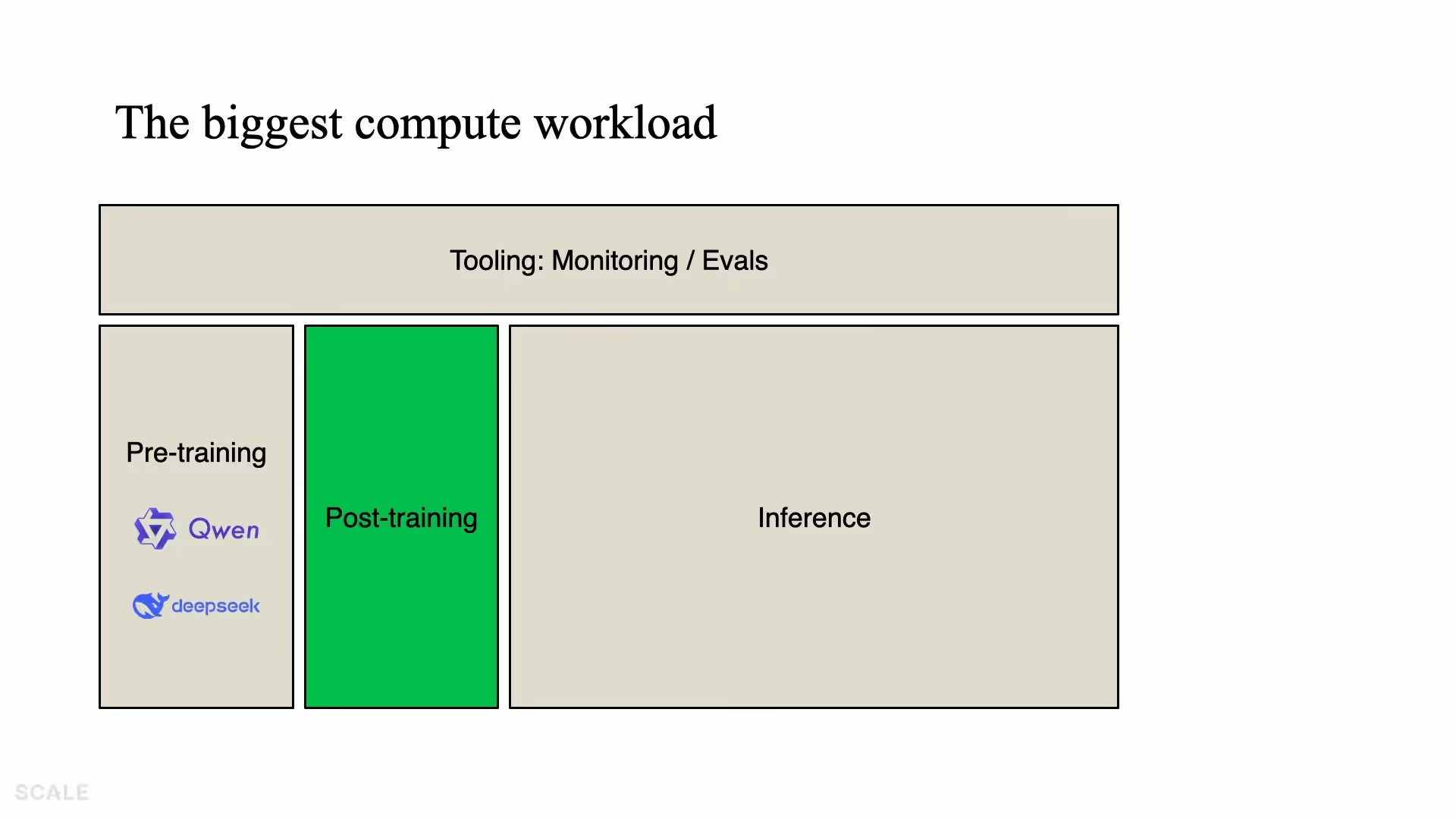

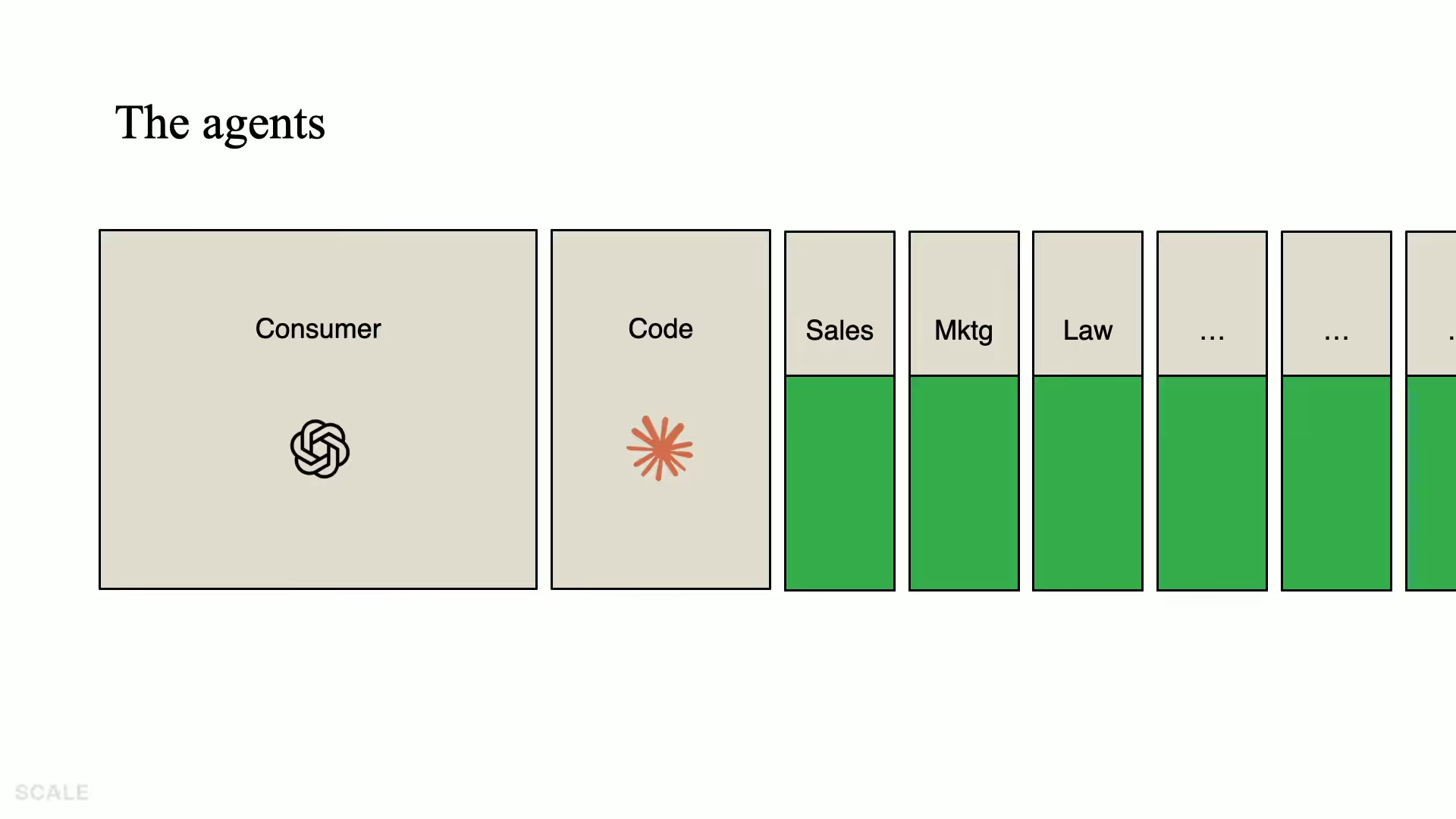

Now let’s consider how this affects those who build in AI, and those who invest. Pictured are the relative sizes of the AI use case markets. All of these run on the same proprietary models trained on the same public data. Now let’s see where these agent builders spend their money to improve those models.

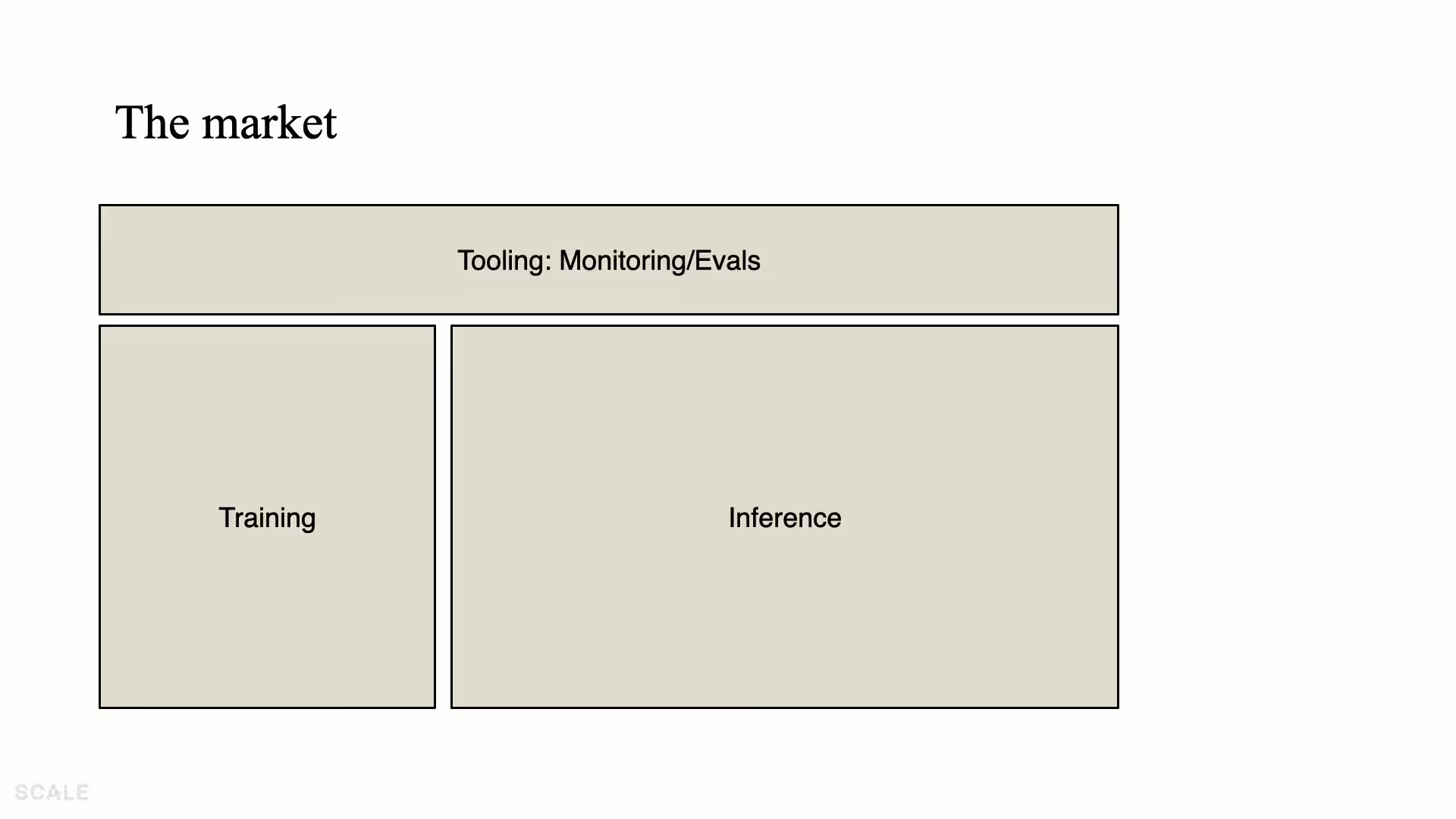

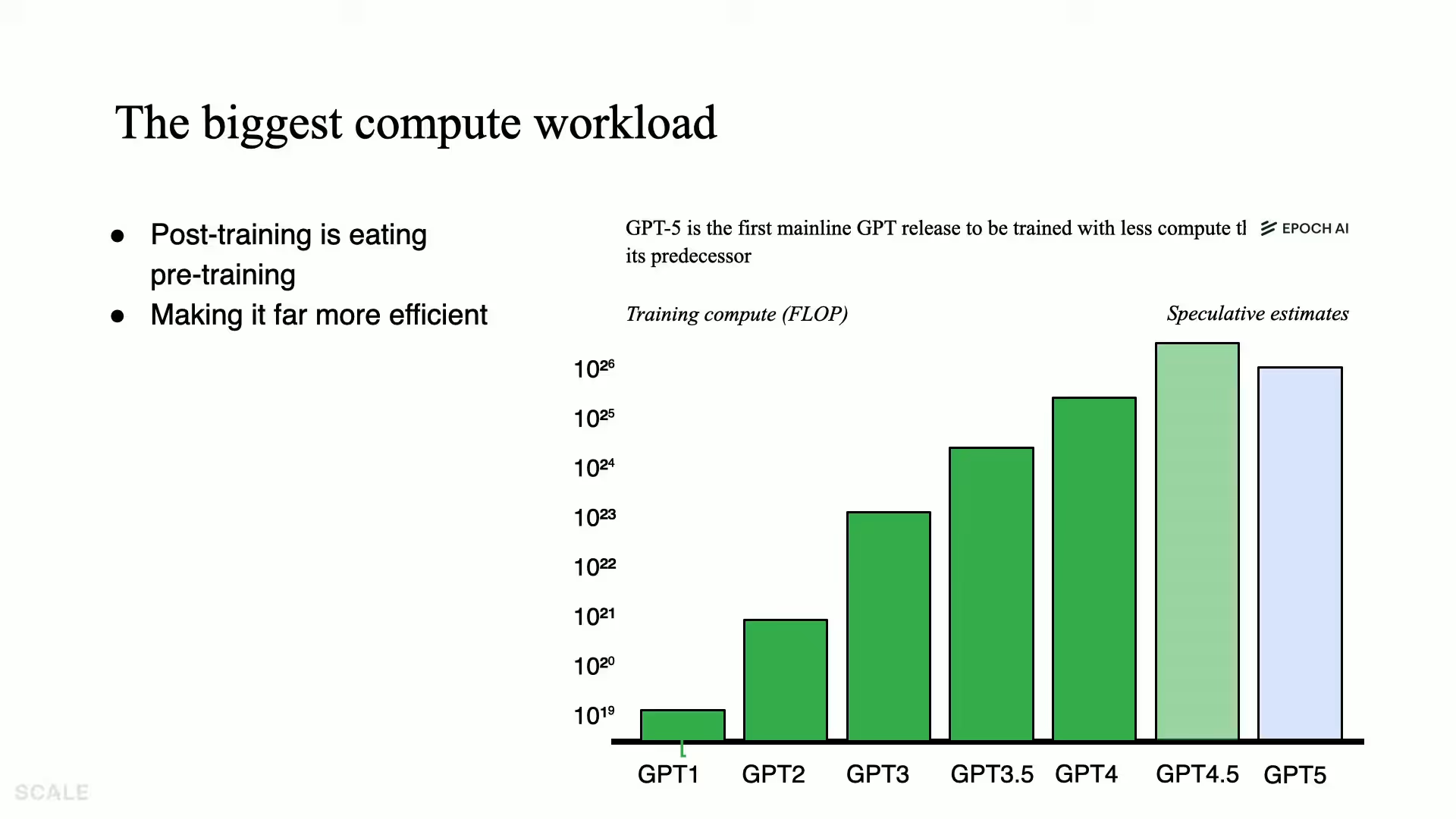

The graphic below is intended to be illustrative of market size. Compute is the biggest expense and here we’ve divided it into training and inference. The models are trained, then put on an inference provider, then all the prompts and requests happen on that interface.

Training is a huge market. But inference is even bigger and just unfolding. And then on top of that, we have the tools that agent builders use. They’ll monitor their agents and evaluate their progress. If models keep costing orders of magnitude cheaper than prior models (e.g. GPT 5 costs less than its predecessors), we will likely see that post-training will eat some of pre-training. And then inference. If that happens, this will effect a big shift in where the opportunity lies.

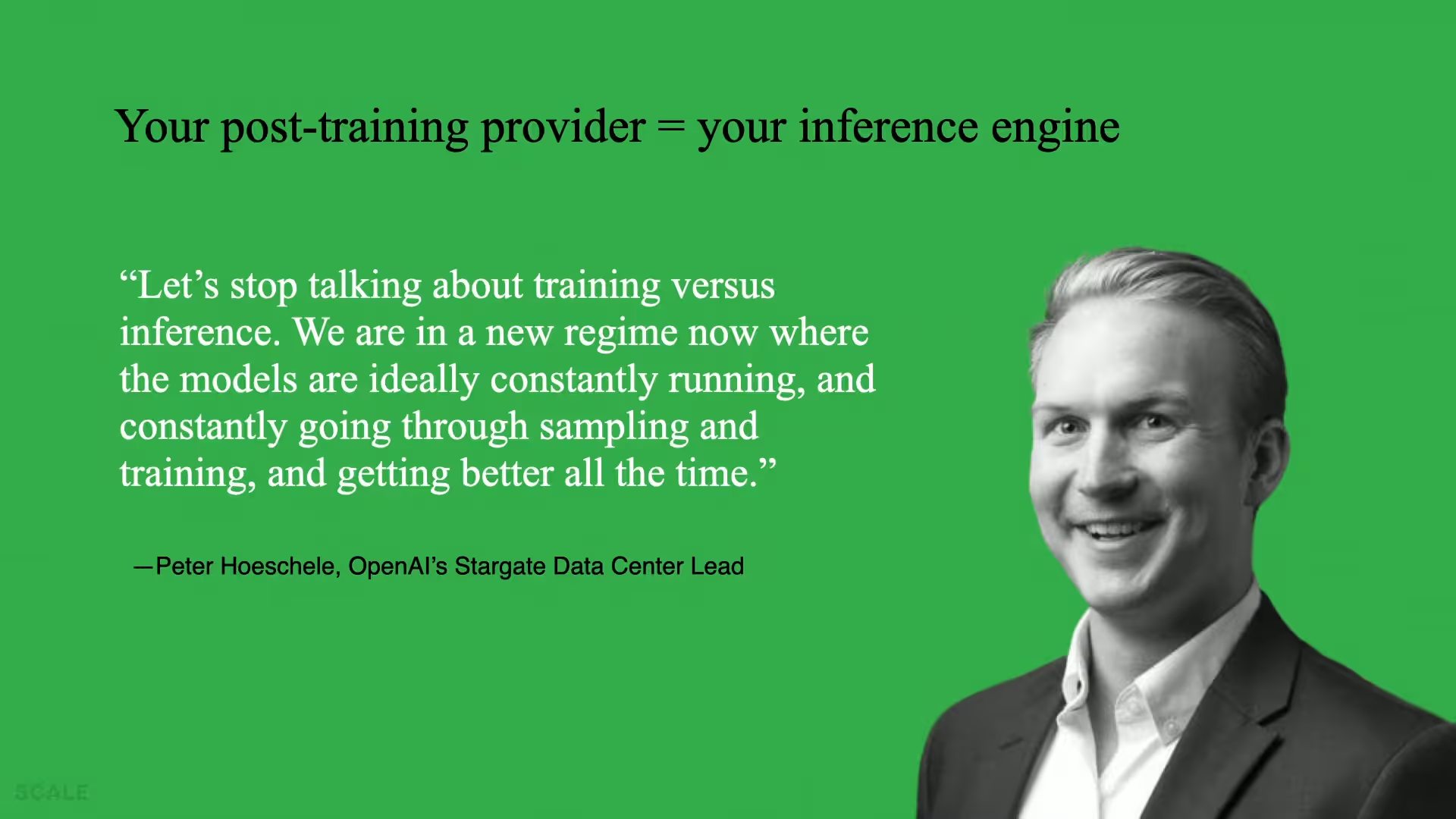

To quote OpenAI’s lead on Stargate, we need to stop talking about training versus inference. Models are now constantly going through sampling and training to improve. They are learning from experience. The Open AI team realizes that when they train a model and then they post train it, they do some inference, then they post train it more, and then they do more inference. Then when they post train two different models and do inference on both, they’re routing traffic to all of these and post-training and inference get intertwined, at least in the user experience.

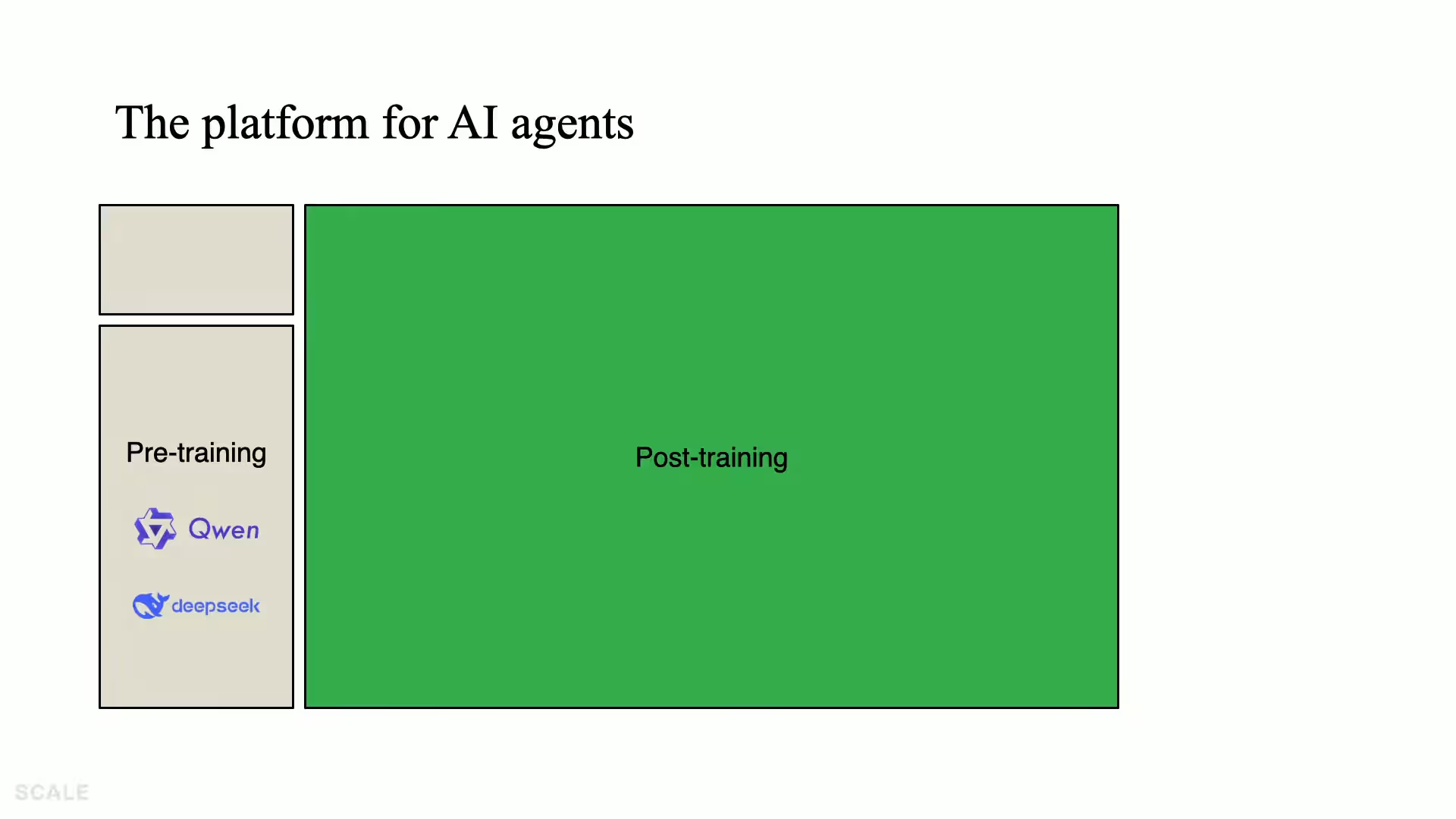

So if they do become one big market, who wins? Is it the inference providers that add post training? Or is it the new post-training providers adding inference? We believe it’s the latter. The post-training companies will win because it’s the new difficult thing and everyone has inference providers. They’re somewhat commoditized. But you also have the new post-training provider because it’s upstream from inference and you get an already awesome model that can offer you inference—they can effectively cross-sell you that.

And then we believe the post-training will start to consume your evals and monitoring suite. What you’re looking at is the future platform for building AI agents. It doesn’t really exist today, but we can imagine it being half of GDP growth in the increased AI data center spend.

GPT wrappers are back

While the major models continue to search for their algorithm twos, the GPT wrappers that felt so vulnerable to these agents just a year ago now have their algorithm two. Sales and marketing agents can actually outperform the core models and if they generate enough proprietary data and earn enough market share.

So while these are smaller markets, reinforcement makes them more defensible. That, we believe, is the frontier of building new agent models.

News from the Scale portfolio and firm