Making Sense of a Crazy Year in Open Source

We’re about a year past the April 2018 IPO of Pivotal, at the time the largest-ever listing of an open source software company. And what a year it’s been for open source. There were the big deals like Salesforce’s $6.5 billion acquisition of MuleSoft, the $34 billion acquisition of RedHat by IBM, the merger of Cloudera and Hortonworks, and so on. At least no one is questioning the legitimacy of open source anymore.

But what’s far more interesting and complex is what has been going on with licensing changes around the industry. At least a half dozen major open source projects have made changes–and in some cases reversals to those changes–to their open source licenses. Today Scale portfolio company Chef is the latest to announce changes to its open source strategy.

Keeping up with what’s going on is not easy. So I wanted to share some observations about developments in the open source industry over the past year, and use that to examine today’s Chef news. I really think the company is doing something very different and very exciting.

The road to open-ish source

“Open core” evolved as one of the primary ways for companies that maintain an open source project to make money. They offer a product that at the “core” is the open source project, but with features that only paying customers have access too. MongoDB and Elastic, which both surprised many people with strong public offerings last year, are examples of this model. As are companies like Redis Labs and Confluent, which are themselves on the path to IPO.

In the last year, all four of these companies have created a middle 3rd tier of code alongside their open source and closed proprietary codebases. Talk about this middle, open-ish tier has consumed the open source community and eaten up news cycles.

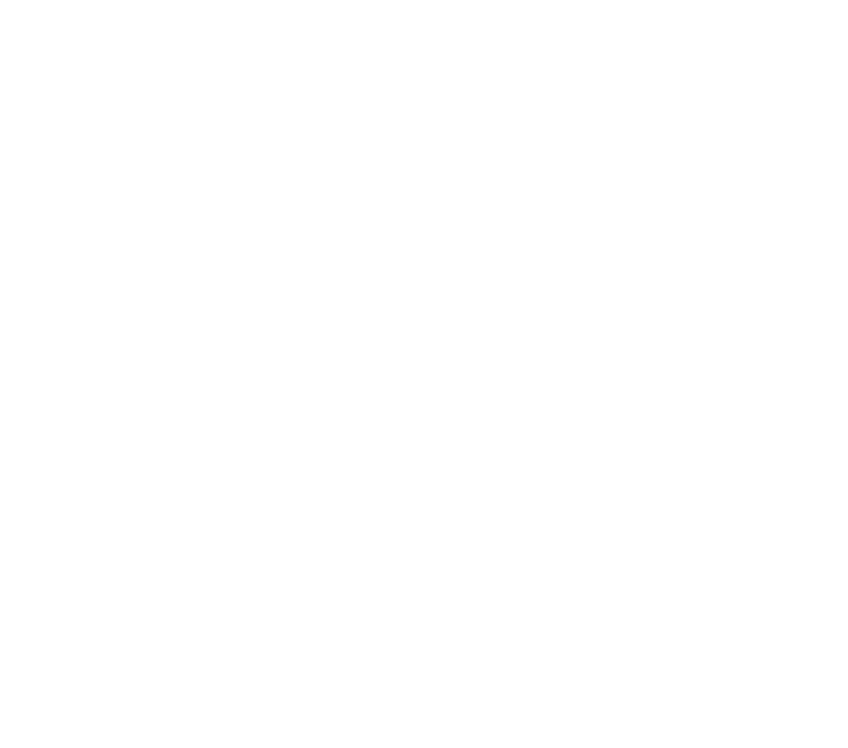

I put together a table detailing what changed with these licensing shifts as well as the primary causes of the often heated discussions taking place in each community.

How did we get here? It started with Redis Labs and MongoDB. Both already had a separate middle-tier codebase with a unique license (AGPL) intended to exclude cloud providers like AWS from competing with them. But when legal experts and others began to challenge that assumption, Redis Labs announced they would be adopting a new one (Apache 2.0 with Common Clause) that others were also adopting. The community, including the influential Apache Foundation, was a bit confused by the license and Redis responded by creating a new license (Redis Source Available License, RSAL). MongoDB similarly created a fresh license (Server Side Public License, SSPL) to mitigate competition. With Common Clause out they hoped SSPL would be a standard and considered “open source,” but withdrew its application before securing Open Source Initiative (OSI) approval.

Confluent‘s core project, Apache Kafka, is owned by the Apache Foundation, so on paper it has fewer degrees of freedom to make licensing changes. Or so it seemed. Confluent had developed other open source (Apache licensed) features that they hadn’t given to the Apache foundation, which they decided to make semi-proprietary under a new Confluent-specific license (the Confluent Community License) that avoided any attempts at a standard.

While others were trying to make their code less open, Elastic went the other direction and published the code behind their proprietary features. Rather than separate code bases with clear licenses, they put the proprietary code alongside open source code in a single dual-licensed codebase. The confusion and outcry from the community led AWS, Netflix, and Expedia to fork the project, creating a new distribution of just the pure open source pieces.

Three-tier licenses are the new normal

Remember, all of these developments have taken place in just the last year. And I’ve only just skimmed the surface — I haven’t even touched on the responses from the various communities. The community responses range from reactions to making code semi-proprietary to complaints about poor standards and attempts at appearing to be “open source.” Elastic made things more open, Confluent made things more closed, but Confluent got less flack because they were the last to move and learned not to call it open source and own what they were doing.

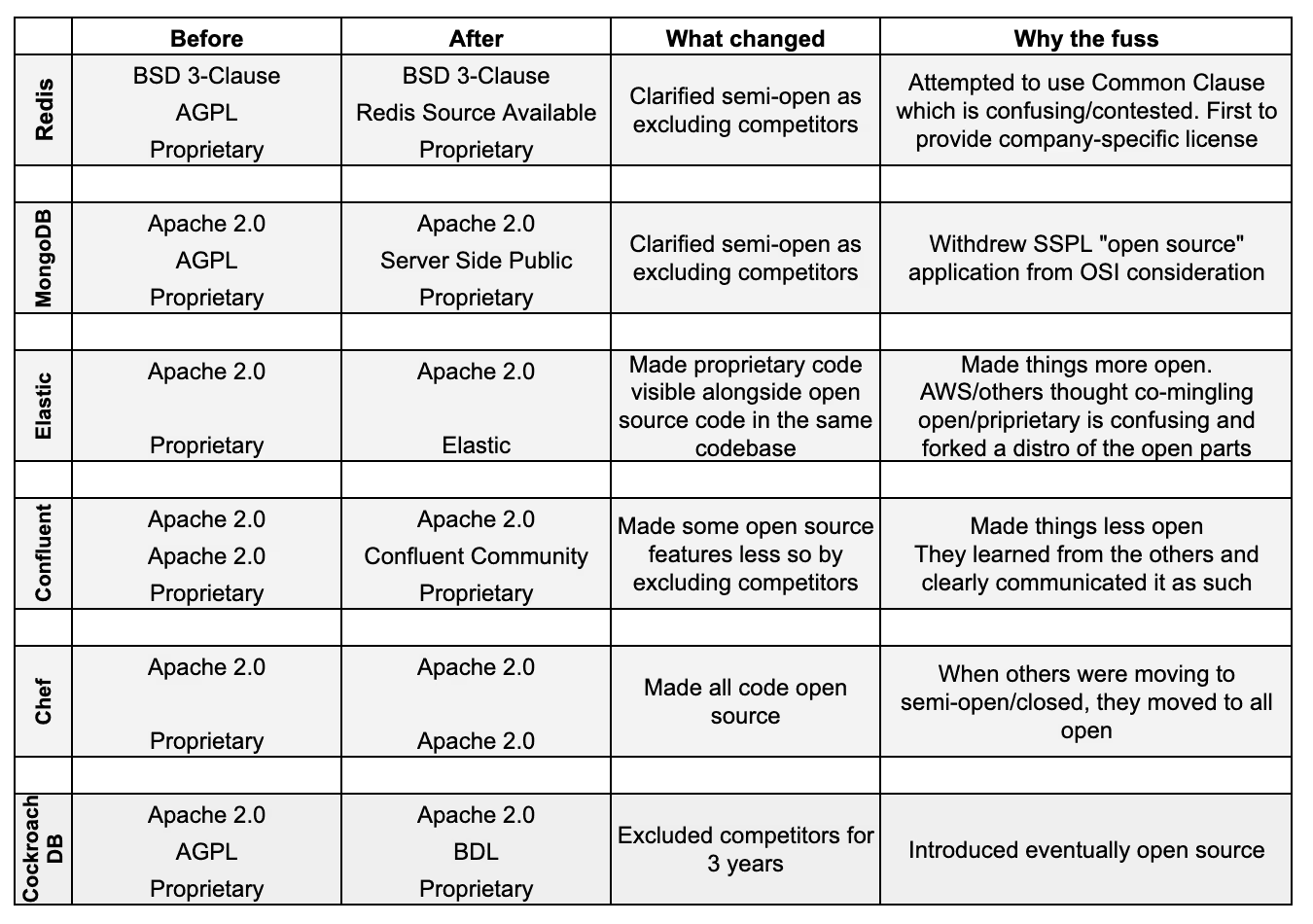

Speaking about the new normal of 3-tier products, Elastic CEO Shay Banon summed it up, saying “We now have three tiers: open source and free, free but under a proprietary license, and paid under a proprietary license.”

You see the same high-level licensing structure in Confluent and Redis Labs’ offerings as well.

Source: Redis

Source: Confluent

It is into this new 3-tier world where Chef, also open core and also facing the threat of competition from cloud providers, has gone the other direction and streamlined and simplified their open source offering. I’d go so far as to say the Chef news revitalizes the early spirit of open source software development: all Chef software will be developed in open source under the Apache 2.0 license. No asterisks or caveats.

I see this move as an important milestone for the company, also an interesting watermark for open source in the industry. For the past year I’ve wondered if fully open source or even simple 2-tier open core would become something of the past. Chef’s announcement restores some hope in the model. Time will tell whether others follow and what resonates with both the community and market, but for now I’m going to enjoy the easy collaboration within the Chef community.

News from the Scale portfolio and firm