Tech Valuations In 2016: The End Of The Line For Sloppy Growth

This post originally ran in TechCrunch

What’s going on in technology investing right now? Is this another 2001, when tech imploded? Another 2008, when the wider world crashed but tech powered through? Or is it like Facebook in 2012, a valuation blip and a chance to buy?

Anecdotes about dead unicorns are not enough. An explanation has to start with a framework and a qualitative description of what is driving the markets — then back up that model with data. This is my model and my data.

Valuation and burn drive it all

Venture-backed startups live in a crazy hyper-cyclical world driven by the constant and mutually reinforcing dynamics of burn and valuation. It is easy to sound like the elder statesman “worried about high burn” or “worried about high valuations,” but tolerance for burn and willingness to “pay up” for high growth are core aspects of the entire venture model.

The question is always whether the money being spent (burn) is creating enough fundamental value (revenues, customers etc.) to justify the high valuations. From that perspective, absolute valuation (billion dollars, yes or no) is the wrong metric on which to focus. It is an output, not an input — and it is extremely prone to overshooting, with the last five years being a clear example. In that period, capital markets have been in love with growth.

High-growth companies have attracted high valuations, which allowed them to raise capital, which was then spent to generate still more growth and raise the valuation again. The result has been a self-perpetuating cycle of high burn, higher growth, still higher valuations and a strong positive feedback loop.

This puts pressure on companies to keep that growth going at all costs. Because the number of profitable ways for a company to spend money is finite, at some point that pressure to grow leads to investments that deliver growth, but at the expense of profits. Unprofitable sales channels, subsidies to acquire customers and expensive advertising campaigns are all signs that a company is focused on growth at all costs rather than growth at a profit. Companies get sloppy.

The slop has been showing up in the numbers

The basic financial model for every technology company is the same. Spend a fixed sum of R&D dollars to develop a product, then start spending on sales and marketing to generate revenues. The hope is that (eventually) the revenue generated from customers, less the sales cost required to acquire those customers, will be large enough to cover R&D and other costs, and the company can become profitable.

That is why all conversations about “burn” quickly become conversations about customer profitability. All other expenses are roughly fixed, and the speed at which sales expense yields customer revenue is the key financial metric for the company. If something is going wrong, it will show up here.

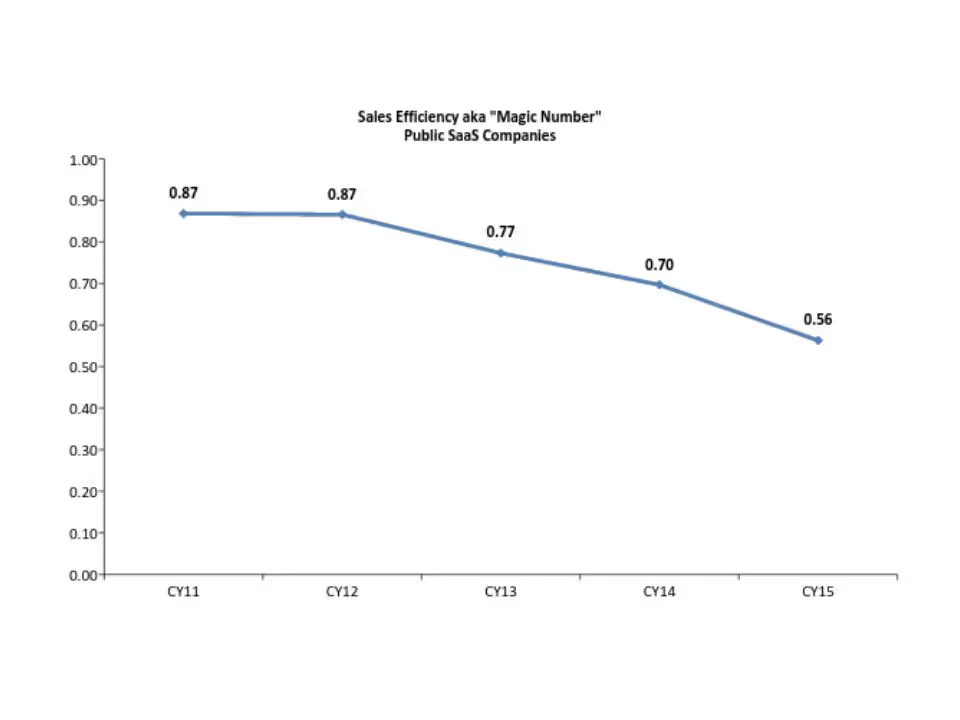

It already has. For SaaS companies, which is the area I invest in, the simplest and most accessible measure of customer profitability is Sales Efficiency, the ratio between quarter on quarter revenue growth and the sales and marketing costs required to generate that growth. The chart below displays the median Sales Efficiency for all public SaaS companies from 2012 to 2015 YTD.

This is the key measure of value creation for these companies, and it has been declining fairly consistently since 2012 (and is now about 35 percent below the peak, with a rate of decline that is accelerating). This is a huge deal. Customer profitability is the transmission mechanism from burn to growth and from growth to valuation. This key metric has been plummeting just as more money was being poured in.

Values crashed almost 2 years ago

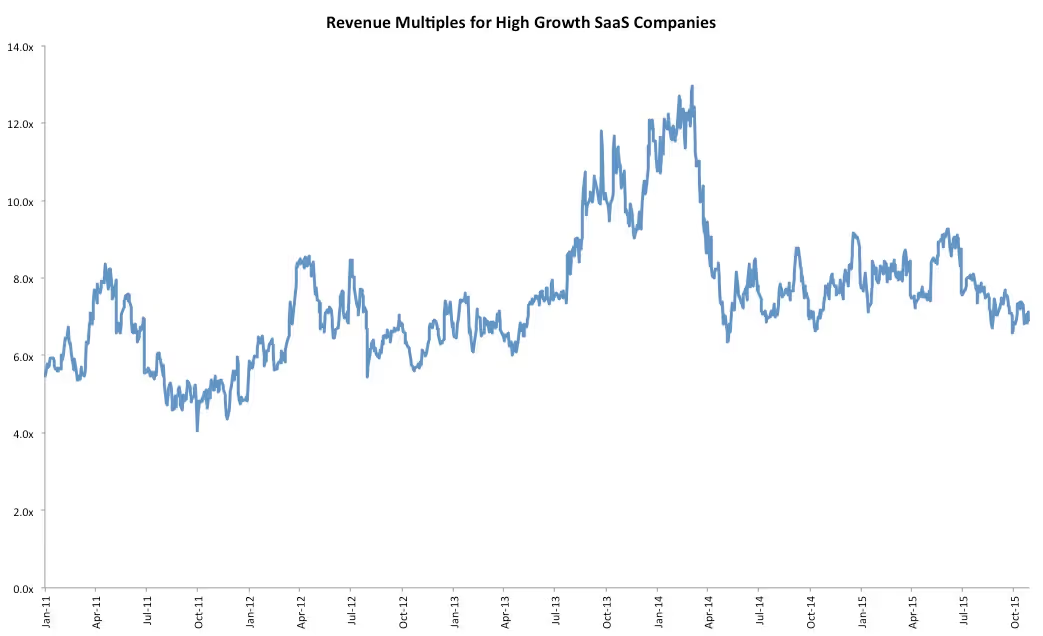

The public markets figured this out almost 2 years ago. Looking at the same public SaaS companies, the chart below looks just at the top 25 percent of these companies ranked by growth, and shows how they are being valued over time.

In March 2014, these high-growth companies were being valued at 12x run-rate revenues, but by mid-2014, this had declined to around 6x revenues, which is where it has remained since. The long-expected crash has, in fact, already happened.

The two are connected

Either you believe in remarkable coincidences or it is clear these two charts are linked. Unlike the private markets, the public markets get to rethink investment decisions every day. Over time, public investors either explicitly or implicitly realized that customer economics and the quality of growth have declined and, consequently, reduced the premium paid for excess growth. Capitalism works.

The private markets, where decisions only get made once a year, have been slower to react; hence, the dearth of IPOs and the price adjustments seen as high-priced private companies come to the public markets.

What now?

In 2016, any private tech company where the last percentage points of growthhave only been generated at the expense of profit will no longer be able to attract capital at a high valuation. Smart companies will respond by cutting marginal investment, thus raising sales efficiency — even at the expense of having a lower growth rate.

We will then see the same feedback loop kick in, but in reverse. Lower valuations will result in less capital being raised, which will result in lower growth and still-lower valuations. In contrast to the rise, the decline will happen much more quickly. Bubbles build up slowly, crashes happen fast. Eventually it will bottom out as growth rates become sustainable at acceptable levels of customer economics. Sloppy growth will be out. Sustainable, smart growth will be back — at least until the next time.

Casualties along the way

The new end state will be fine, but the transition will be hard. Some companies will have left it too late to switch paths and will run out of cash. Even for the vast majority of companies that make it, management teams and investors are looking at one to two years of what is euphemistically called “growing into the valuation.” This is another way of saying working hard for no additional return!

It is not 2008, which turned out to be ugly for the world but fairly benign for technology; it is not 2001, which was a bloodbath for tech; nor is it Facebook 2012, a panic over nothing. The industry has overpaid for, and over-invested in, reasonably good companies. Now all involved have to take their lumps and settle back to a slower growth, but saner world. It’s not the worst thing that could happen.

News from the Scale portfolio and firm